I glanced at the clock again. It was almost time for Maahi, my granddaughter to arrive. It was raining hard. I sat by the window as the song ‘Bade acche lagte hain’ by R.D. Burman played on the radio. Rain, RDB on the Radio and I’m in a trance. If only, I had a cup of chai to go with this reverie.

Just then, the doorbell rang, and there she was. With two cups of chai and keen eyes, waiting for today’s episode of adventures in Kalyan Moti Ni Chawl at Kandawadi in Mumbai. Overwhelming feelings of love, nostalgia and gratitude prevailed as I told her one story after the other.

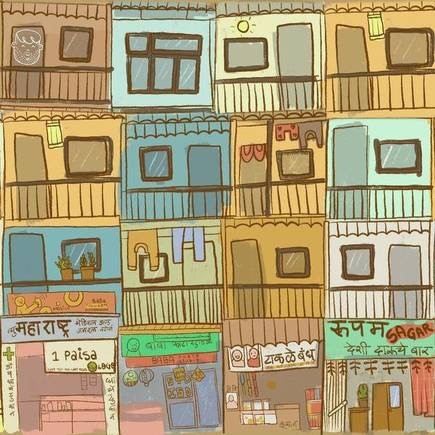

Growing up in an isolated and urbanized environment like Maahi did, I started from the very beginning. The word ‘chawl’ is an anglicized version of the Marathi word ‘chaal’ and refers to the type of residential housing typically built for the working class in western India. Kalyan Building had 300 rooms spanning across 8 buildings. Everyone knew everyone. Relationships grew, evolved and flourished. Adults and children alike found humor and joy in the little things. And the door was always open.

Life in the chawl system internalized and embraced the idea of co-existence. The Maharashtrian and Gujarati communities lived together harmoniously whether in moments of celebration or crisis. During the Samyukta Maharashtra movement (1) in 1956, a group of goons entered the building, threatening the Gujaratis to leave, yet there seemed to be no conflict amongst the residents themselves. “Ame Akhi raat jaagta,” (We would stay up all night) I told her, “We would patrol the entrance of the building, to guard the families in case of any threats or mishaps.” When someone tried to light one of the buildings on fire through a container filled with kerosene, my friend splashed water on his feet and kicked out the container. “Jabardast hato ha, amaro Shashyo.” (One of the most daring people I knew, Shashyo) With the good triumphing evil, each festival was celebrated with utmost excitement and joy. When the wood was not enough to light the fire during Holi, chasing horse-carts and stealing the hay seemed to be the only solution. The togetherness during Diwali was further enriched when they would go to each of the rooms to eat the mithai and sweets offered by the families.

When 300 children, came down to play cricket, competition was a must. I took immense pride in the fact that that our team from building number 7, would be amongst the top contenders in the inter-chawl competition that took place every Sunday. Whoever won the match, would win the ball used during the game. Books and academics meant little, when we played games like Sakli (Chain), Nargolyo (7 stones), kho-kho, Langdi, Kabaddi and evening turned into nights. It is often said that, necessity is the mother of invention. We invented our own games such as ‘goti-bat’ or mini cricket to play in the 120 by 120 feet common room that lay beyond each corridor of flats in the building. Teen-patti was an all-time favourite game but “Baapa paisa thodi aape,” (Do you think our father gave us money?) pocket money was a rarity. She was a little beyond surprised to know that we played for cigarette packets that we would scrounge for at the Royal Opera house theatre (Since it was the only theatre at the time to allow smoking).

She was bemused when I told her, “Mane 365 divas mathi, 200 divas maar padto!” (My father would hit me 200 out of 365 days in the year) Even today, my friends are in awe by this new-found calm and composed nature of mine for they have only known me for the trouble-maker I was. A monthly pass for the local train at the time would cost a mere Rs.3, which could be used for an unlimited number of times. During the rainy season, we would pick up eaten corn cobs, enter the train at Charni Road and throw them at pedestrians on the street. We would cry, beg and plead our way out when one of us was travelling without a pass, and was caught by the ticket collector on the Church-gate station platform.

I was never one to excel in studies, nor did I care for it. One day, my teacher in a last attempt, resigned to giving me the question paper for an exam. That day, I went around the building sharing the questions with all my friends. An enraged Saroj Ben, came up to the house to hit me, only to get a swollen hand on hitting the iron cupboard, as I ducked and narrowly escaped the beating. Laughing a little harder, I gently patted Maahi’s shoulder saying, “Bachha, ame toh bau tophani karya chhe.” (We’ve played a lot of pranks in our time)

The clouds got darker and it started raining heavier than before. “Dadu (2), 65 years is a long time for a friendship. How did you maintain them so effortlessly after all these years?” Maahi asked me. I recalled the day when Motabhai (my father) died. By this time, we had moved out of Kalyan building and so had a lot of my friends. In waist high waters, every single person from the building was there to help me carry the body to HN hospital at Chandanwadi. And this, was only one of the several instances of solidarity and lessons of true friendship that I had experienced. According to a study conducted in the US, most friendships last for 10 years on an average. Mine have lasted a lifetime. “Whatever I am today, is because of Shankar, Haresh and Ramnik.” With a rent of Rs.70 per month, I made invaluable memories. Memories to last a lifetime and beyond.

Sometimes, before we move ahead, we need to look back. We find stories from yesteryear in the nooks, corners and memories buried in the minds of people in our own home.

The chawl system has become a symbol of strength in solidarity and a catalyst of celebration. In the ever-changing city of Bombay, life in the chawl system serves as a reminder of simpler times, rooted in intimate relationships and diverse Indian culture. I’ve seen it all, the ups and downs everything in between and yet lived a life without regrets. “If I were to take birth again,” I told her, “I’d want the same Kalyan Building, the same friends, irrespective of money.”

- Samyukta Maharashtra Movement commonly known as the Samiti, was an organisation in India that advocated for a separate Marathi-speaking state in Western India and Central India from 1956 to 1960.

- Dadu: a term of endearment for one’s paternal grandfather

Maahi Shah is a lot of brains, talent and words. We dare you to find a match or just shut up and listen, sit down and read or stand agape.

DISCLAIMER: The content on this website is merely an opinion and not intended to malign any religion, ethnic group, organisation, company or individual. Nothing contained herein shall to any extent substitute for the independent investigations and sound judgment of the reader. While we have made every attempt to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the content contained herein, no warranty or guarantee, express or implied, is given with respect to the same. The SHOUT! Network is neither liable nor responsible to any person or entity for any errors or omissions, or for any offense caused from such content.

In addition to the above, thoughts and opinions change from time to time… we consider this a necessary consequence of having an open mind. This website is intended to provide a semi-permanent point in time snapshot and manifestation of the various topics running around our brains, and as such any thoughts and opinions expressed within out-of-date posts may not be the same, or even similar, to those we may hold today.

Feel free to challenge us, disagree with us, or tell us we’re completely nuts in the comments section of each piece. The SHOUT! Network reserves the right to delete any comment for any reason whatsoever (abusive, profane, rude, or anonymous comments) – but do SHOUT! with us, if you will.